The methods for decarbonizing our lives are well known: Eat less meat, drive less, travel less, electrify your home and car. Yet it remains an awkward topic. Right action is good, but purity is obnoxious, and virtue is an imposition on one’s desires. We want what we want, and we can afford some of it.

Plus, life is short. It’s difficult to burn less carbon in one’s life and poorly received if you suggest it to others. It’s like getting on the scale when you know you’re a bit overweight, or telling a friend that they should lose some pounds. Unwelcome; seldom done.

There’s some danger that raising the question of how we live risks shifting the burden of change away from governments and corporations; and individual action can do only so much, given civilization’s current infrastructure. An individual’s most powerful form of action remains politically supporting laws to curb emissions.

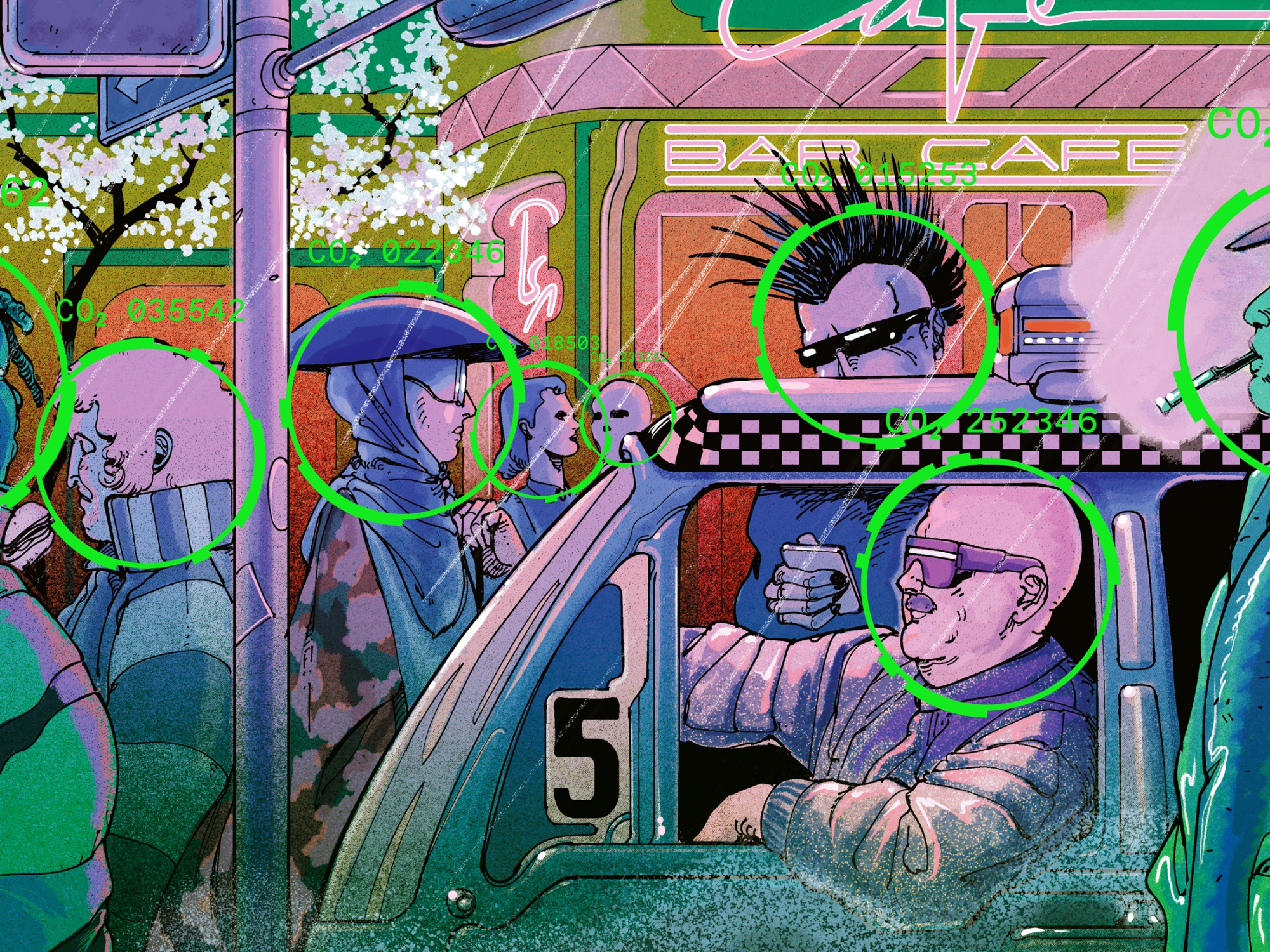

But everyday life belongs in the larger movement because now we are in climate change, the polycrisis, the long emergency. What’s needed to drive rapid change among prosperous citizens is a basic change in attitude, a philosophical shift of values — enough personal action to create a new structure of feeling, in which new behaviors become normal. Then reduction of carbon becomes not a decision but a habit, the done thing.

One approach is simply to become more aware of what you consume. You can calculate every part of your household’s burn and identify where you simply waste carbon. This capability has been with us for at least 20 years. It gets more immersive as households add solar panels, becoming both producers and consumers of energy. You end up paying closer attention.

There are other means of inventing new habits. The 2,000 Watt Society, based in Zurich and Basel, made a typically practical Swiss calculation to start the process: If you divide all the energy available by the number of humans alive, the annual amount available to each person works out to around 2,000 watts. (For reference, Europeans typically use about 6,000 watts per person; the Chinese, 1,500; Bangladeshis, 300; Americans, 12,000.)

What would it feel like to live on 2,000 watts, and thus use only your fair share? The Swiss who tried it found it’s not bad. They experienced no great deprivations and reported the extra satisfactions of living not only virtuously, but also stylishly. Daily life became an accomplishment, an aesthetic act, like performance art.

This brings us back to a basic philosophical question: How best to live? As the Dalai Lama once remarked, we all will burn some carbon just by being alive, so it’s not a matter of renunciation, but of mindful consumption, much like mindful breathing. Paying attention to what actually feels good, as opposed to what is supposed to feel good, can be very instructive.

Following the nudges of the advertising industry, and thus burning carbon like lighting cigars with $100 bills, is not as satisfying as sitting in the dirt weeding a garden or sitting across a table sipping coffee with a friend. Watching isn’t as satisfying as doing. The virtual isn’t as satisfying as the real. Being animals, our animal pleasures are the deepest, and those pleasures burn less carbon than the virtual, mediated, boosted and advertised pleasures of the consumption society. That’s simple biology, and it’s a good thing, too, for us and for the rest of our family, meaning the biosphere.

So pay attention; feel your body; think it over. Be mindful of your carbon burn, and make what you burn really count. Don’t waste it. We’ve been cocooned in fossil fuels for too long, and busting out of that sheath of crap back into the wide world will be a liberation.

Kim Stanley Robinson writes science fiction in Davis, California. Read and share the full version of this essay on the web here.